Last week, in the depths of winter, a day after the lab was shut because of a snow day, my research group went out in a ship on the Gulf of Maine. This was the first time we had managed to get out during the winter in two years. Winter is a hard time to do field work in the Gulf of Maine, the sea states don’t normally calm down enough for us. But we got a 2 day window, and took it.

My boss, Dr Barney Balch, has been running the Gulf of Maine North Atlantic Time Series, or GNATS as it is better know, since 1998. One of the main goals of GNATS is to validate satellite ocean colour data. Scientists use satellite ocean colour to study life in the oceans by e.g. saying “the Gulf of Maine is green just now, that means there must be this much algae in the water”. But we need to check that the satellites are seeing the correct thing, because it can be hard to interpret what materials are in the water based on its colour. So on GNATS, we try to go out into the Gulf of Maine on a clear day, when the satellites are passing overhead. We measure the light, or colour, of the water, just as the satellites will, and we measure a bunchof other parameters which tells us about what is in the water (e.g. algae) and what it is doing (e.g. how much carbon are they fixing). Then, we can check the satellites are giving us correct estimations about what is in the water.

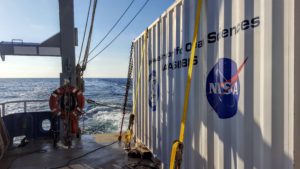

So how do we do this? We have a small shipping container fitted out as a portable laboratory, which we can put onto a ship. The container is connected to a seawater intake, and the water is then run through a suite of different instruments. We also put some radiometers on the bow. These measure the light coming down from the sky, and the light leaving the water – giving us a measure of the colour of the water. We also measure the temperature of the full water column: from the surface down to the seafloor.

Over the summer months, we use the passenger ferry that runs from Portland, Maine to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. We can just drive the “Van” onto the ferry, connect to the water intake, and we are all set. Using the ferry is great because we can just watch the weather, and if it is clear, we can go for it. In the winter, we typically use the University of Connecticut’s research vessel: R/V Connecticut or the UConn. We have to lift the container onto the aft deck of the UConn, and normally we don’t get as good a choice about the weather! Unfortunately on this trip it was cloudy, but it is still important to get measurements in the winter to look at how the Gulf of Maine is changing year round and over the 20 years of the time series.

It was fun to get out of the lab for a couple of days and spend the night on the ship. We don’t get to do that in the summer when we use the ferry.

I was lucky enough to see some Saddleback Dolphins swimming alongside us early in the morning.